Madison Beer does what she wants these days, and what she wants right now is to please not sit in the tiny, iron-barred former strongroom set aside for our interview at the back of a pub in south London.

‘It’s like a prison cell,’ the New Yorker mutters, refusing to even set foot in the space. The pub is a converted 1960s post office, I explain. It’s supposed to be a trendy nook. ‘It’s not, it’s creepy,’ she corrects.

We find a less oppressive sofa and chairs nearby, on to which Beer flops backwards, burying her hands in the pockets of a huge pastel, faux-fur coat, and pulling it so far across her minuscule frame that only her head and long dark hair poke out. Once settled, she is very cold: is there heating on? She is not thirsty, thank you. Not even water, no. And can they turn the music down in here? It’s, like, really loud.

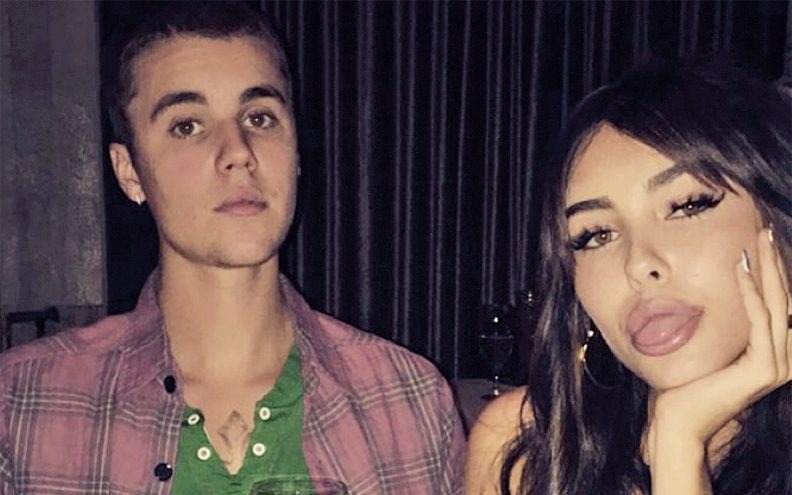

Beer is just 19 years old, but already in the early stages of her second run at becoming a world- famous pop star. The first began six years ago, when her idol, Justin Bieber, saw a YouTube video of her covering Etta James’s At Last and recommended it to his millions of acolytes on Twitter. ‘Wow,’ he wrote, ‘13 years old! She can sing. Great job. #futurestar.’

It was like being anointed by God. Within two weeks, Bieber, then the world’s biggest pop star, had got Beer signed to the world’s biggest record label, Universal, and given her the world’s most influential pop manager, Scooter Braun (both were also his own) to ensure she had the best chance of success. Beer quit school and moved to LA with her mother and brother. Bieber appeared in the video for her sickly sweet, terrible debut single, Melodies. And then, when that song wasn’t the global mega-hit everybody expected, Beer was simply ‘put on the shelf’. For three long, grim years. She left Universal by mutual consent at the age of just 16.

‘I think it was just wrong timing; if I was signed to them today, I’d be huge,’ she says, in an accent that’s so coast-to-coast, so Gen Z, that everything she says sounds as if it comes with a shrug. ‘They didn’t really know how to position me. People would expect me to be this ditzy, bubble- gum-pop girl. I was selling myself short. I would now rather be less successful, fame-wise, than be the biggest thing in the world and a lie.’

The whole experience could easily have put Beer off the music industry for life. After all, the received wisdom was that no label meant no chance, especially for female artists. She could have slipped back into the sea of anonymous wannabes as quickly as Bieber fished her out, and nobody would have blamed – or remembered – her at all. Only she didn’t do that. Instead, she realised the received wisdom was ‘bullshit’.

Inspired by huge fan support on social media, Beer became her own boss, joining a generation of pioneering (and mostly male) young musicians who are finding success without the help of a label. She noticed that Instagram – where her following is now the size of the population of Rwanda – was becoming the most effective weapon in a modern pop star’s promotional arsenal, allowing complete image control and a direct dialogue with fans around the world.

She cottoned on to streaming giant Spotify’s decision last year to start making direct deals with artists and managers, circumnavigating the record executives, so that songs could land on influential playlists before they’d even had radio play. She rebranded herself, embracing a ‘girl boss’ tag and making music that was darker and sugar-free, ‘like a witch with superpowers, sprinkling female empowerment’.

She sought a manager, Sarah Stennett – a Liverpudlian with a proven record of launching young female artists (Rita Ora, Ellie Goulding, Iggy Azalea) – to help her. And now, by deciding on her own songs, brand and image – plus, crucially, understanding that the way music is consumed by her generation is changing at a pace the label bosses can scarcely keep up with – Beer is showing that you don’t need to be signed to be heard any more.

I honestly believe going independent is the future. Social is changing, Spotify is changing, everything is changing,’ she says, firmly. She’s certainly being heard: an EP Beer released a year ago, the pointedly titled As She Pleases, has been streamed more than 450 million times. She has over 10 million monthly Spotify listeners – more than her signed, award-winning peers Jorja Smith and Sigrid combined. Her latest single, Hurts Like Hell (co-written with British star Charli XCX), has been watched 13 million times on YouTube.

And perhaps most impressively, last summer she became the first fully independent female artist in US chart history to have a song in the top 25, with Home With You. Stennett calls her ‘a leader of her generation’. In the pub, though, we’re still on introductions.

‘Um, well, I guess I’d say I’m Madison Beer, a pop and R&B singer from New York…’ she says, yawning and trailing off. She turns out to be excellent in conversation – uncommonly honest, arch, and with an eye- roll that could level a village – but takes defrosting. ‘I just love music. I think it’s art,’ she adds.

I’d better take over. Beer was born and raised in Jericho, a small town on the North Shore of Long Island, 30 miles from Manhattan. Her mother, Tracie, is an interior designer and inventor (her principal creation is a new type of coat hanger for halter-neck dresses) and her father, Robert, runs a successful construction company called Built By Beer. They divorced when Madison was seven.

‘I remember my mom sitting me down and being like, “Don’t worry, they’re going to start dropping like flies. All your friends’ parents are going to get divorced.” Two weeks later, my friend Lauren’s parents did. Then Louise’s, then they all did. My mom’s very cool, she wasn’t dramatic about it.’

For the next few months, Beer and her brother, Ryder, who is three years younger, stayed in the family home while her parents rotated living there, before Robert moved to an enormous new home (his family were responsible for building ‘a lot of the mansions in Long Island and Manhattan’) and Tracie to a small two-bed house. It was deemed right the children stay in the bigger place.

‘Between the two, I was going from a palace to sharing a bedroom with my brother,’ she tells me. But which did Beer prefer? ‘Mom’s,’ she says, without pause. ‘I felt her close to me. I felt really alone at my dad’s house, it was so big and scary. But in Long Island people care about how much money you have. Even I did when I was growing up. I never wanted kids to see my mom’s house because I was embarrassed that they’d tell everyone, “Oh, Madison’s mom is poor!” And she was definitely far from poor…’

That Long Island attitude to wealth was most alive and well in her paternal grandmother, Lorraine, a fantastic-sounding woman who drives a Rolls-Royce, hires the Four Seasons for parties and is ‘so bougie, she’s like the female Karl Lagerfeld’. If you google her, you’ll see that comparison is spot on. It’s not an anecdote that will engender global sympathy, but the broad point is that she’d like to earn her own money.

She leans forward. ‘I’ve literally never shared this with anyone, but with my trust fund – I will embarrassingly admit I have a trust fund – I told them I don’t want it until I’m at least 42, and with kids. Usually kids get them at 18, and feel like they don’t have to work because they have millions of dollars waiting for them. I don’t want to live off someone else’s success.’

Beer always dreamed of escaping Jericho, a town where ‘everybody was cookie-cutter, so being yourself was hard’. At school, she was popular but drew criticism from other girls for liking musicals, and for staying in to watch singing videos instead of going to gymnastics.

She had only made three other YouTube covers by the time Bieber found her. A singer since she was tiny, she waited until her braces came off at 12 before setting up a webcam and microphone and recording a medley of Bruno Mars songs, posting it online afterwards. The next day, everybody at school laughed at her, because children are like that, but she persisted, uploading At Last soon afterwards. And we know what happened then.

‘It was like he [Bieber] spun my life around in one tweet.’ On top of the endless media attention, ‘haters and trolls’ made their presence felt across all online platforms, critiquing Beer’s voice, clothes, appearance – verything. ‘It was just something we had to get used to,’ she says.

Today, she insists she has no bad blood with Braun (or Bieber, who remains a friend), understanding that he was perhaps too ‘busy with [other acts] Justin, Ariana and Kanye’ to have time for her. She didn’t even like her first song.

‘It wasn’t what I wanted to do. I’d been signed because of singing something as soulful as At Last, then I was making music that was so different because I was young.’

Her age was an issue in a variety of ways. For instance, it sounds like most of Braun’s job was informing other men it was quite literally illegal for them to fancy her.

‘It happened a lot. One of my friends was at [Braun’s] office when I was maybe 14, and all these guys were talking about how hot I am, and he told them how old I was. Suddenly they’d think it was gross that they ever looked at me, so wouldn’t want anything to do with me,’ she says.

‘I had experiences that were a bit creepy and too much, which I try to blame on, “He didn’t know how old I was,” but really, when you’re in a label meeting, I assume you know how old the artist you’re speaking to is…’

Experiences like what?

‘Like being a little too touchy, hugging a little too long. This was before #MeToo existed and people weren’t openly speaking about that, so a lot of older men didn’t feel cautious. They were like, “Oh, I’ll just flirt with this 15-year-old, no one’s going to say anything to me.”’

Tracie, who by that point had moved to Los Angeles with her daughter, would often be in the same meetings and see it happen. Beer just shrugs as she tells me this.

‘It was hard,’ she says. ‘I wasn’t allowed to be a kid a lot. At all, actually, from the moment that video went up. I make the best of it. I try not to think of it as not having a childhood, but that my childhood was different. Nobody forced me to do it. I wanted to be a superstar.’